Learning to Read from the Brain's Point of View

My daughter, Mairead, was born in Indonesia and we lived there until she was 8 years old. By age 3, she could speak three languages: English, Indonesian, and Sundanese. She learned the local dialect, Sundanese, from her best friend, FenFen, who lived next door. It was very natural for Mairead to learn to speak these languages because she heard them all day, every day.

When Mairead was three-and-a-half years old, we spent an extended summer in America, and Mairead forgot most of her Sundanese. Upon returning home to Indonesia, Mairead rambled on and on in English to a bewildered FenFen, who just stared at her. Finally, a perplexed Mairead turned to me and asked, “Why her not talkin’ to me?”

I have always been amazed at Mairead’s extensive spoken language abilities, although now that she is 14 years old and is constantly on social media, I am the one asking, “Why her not talkin’ to me?”

The spoken language system seems to develop so naturally for most children. Kindergarteners loquaciously discuss what they saw on the way to school without taking a breath. Why, then, is it that the written language system of reading seems so unnatural for children to master?

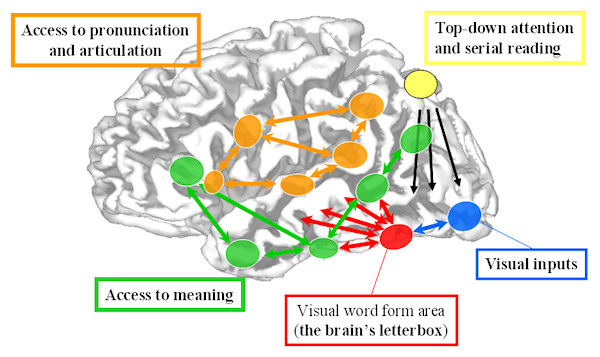

The answer to that is so excellently explained by Dr. Stanislas Dehaene, a French cognitive neuroscientist. Using the plethora of brain imaging/viewing methods available to us today, Dehaene unpacks the dynamics of brain activity and articulates how the brain learns to read. Dehaene explains that although young children’s brains have very well developed networks for vision and speech (blue-visual inputs), the brain must be explicitly taught to attend to the individual phonemes of speech and must attribute them to different letters. This happens in the left hemisphere in the Visual Word Formation Area, or the brain's “letterbox” (red), as Dehaene calls it. This letterbox is activated only in literate people.

The lexicon, meaning system (green) and the pronunciation, articulation (orange) system, are already utilized for spoken language, but there needs to be a connection created between these networks and the networks that code for speech sounds and meanings. Dehaene states, “So we can say, essentially, from the brain's point of view, that learning to read consists first in recognizing the letters and how they combine into written words, and second, connecting them to the system coding for speech sounds and for meaning.”

To get the full story, watch the following video:

So, learning to speak the three languages that my daughter Mairead was immersed in came very naturally for her brain. What we know from neuroscience today is that learning to read those same languages would not come naturally at all. She would need structured literacy instruction to learn to pronounce which sound each letter or combination of letters made (phonemes) and how they combine together to create words that have meaning. The brain mechanisms for learning to read are the same in all cultures.

Although science cannot yet give us the answer as to why our teenage daughters may not be talking to us, it does give us the answer on how to rectify the problem of, “Why her not readin’ to me?”

Learn how Reading Horizons incorporates brain science into practical classroom strategies in our elementary reading program and reading intervention curriculum.

2 Comments

Dad said

Damn! That's good!

Mom Brown said

WOW! What a great blog!! Very impressive. Love. Mom